Croatian artist in Latvian prison

I’m here on a job shadowing opportunity thanks to Linda from Radi Vidi Pats, with whom I share a passion for working with prison inmates. We met in Portugal during an EU project in 2021 and realised that both of us were conducting creative workshops in prisons—a pleasant surprise! Two years later, Linda sent me a message on WhatsApp: "Hey, I’m going to Granada for a partner-building activity where we’ll learn about best practices in youth work in prisons. Are you interested?" Hell yeah, I’m interested! We met again in Spain for the EU project and while we were waiting to enter the prison, Linda asked me in the prison lobby if I would like to come for a month-long job shadowing experience next year in Latvija. The plan was to volunteer at a prison in Liepāja, get to know the organisation and explore Latvia. I think my answer back then is now clear to you. In short, that’s how the journey from the Balkans to the Baltics began.

In Croatia, I’ve been working in prisons since 2018. My first experience in a juvenile detention centre was a practical assignment that led to my thesis and later defending it at the Academy of Fine Arts in the Art Education Department. I felt that too many students were researching methods in primary or high schools, writing their methodological theses about them and that everything had already been written and researched. I wanted to go where there was no "path of least resistance," where no one thinks to go, where some people are even afraid to be. I decided to contribute to a group of juveniles in vastly different circumstances, ones who weren’t tired of students from the Academy and who didn’t have many privileges. It was a way to contribute to society, open new perspectives for my colleagues and myself.

Now, after six years of working in many prisons and holding numerous art workshops, and as the project leader for Ja to mogu - Art Workshops in the Prison System, funded by the Ministry of Justice and Administration and hosted by the Croatian Society of Fine Artists, I understand just how important it was to push for that first entry into the juvenile detention centre, just so I wouldn’t write a dull thesis. I believe art workshops are a key part of the reintegration process for inmates, offering personal development opportunities, self-expression, and the creation of positive interactions with their environment. Creative work, in this case for inmates, benefits their psychological and physical wellbeing, reducing stress and anger, fostering a sense of achievement, self-esteem, lower self-harm rates, and encouraging critical thinking. Working with inmates is essentially working for our society, because most of them eventually return to it. The question is: what kind of society are they returning to if that society doesn’t feel the need to work on the reintegration of inmates in correctional facilities, prisons, and juvenile detention centres?

I would like to tell myself, "Come on, stay positive; our society is great, and we always somehow manage," but I’m tired of hearing lies. Nothing will happen if we don’t do something. Honestly, I think there are too few people who are willing to use their knowledge and skills to improve society, their own environment, or the community. Some people can’t even make their own homes comfortable, let alone work on their society. My guiding thought is that not everyone who has two legs is a person… we need to look within to positively influence those around us.

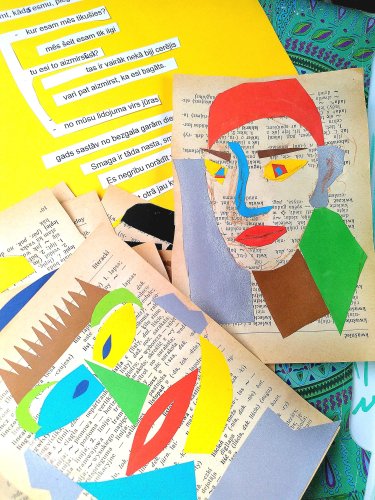

In Latvia, I conducted several art workshops in prisons in Liepāja, Jēkabpils, Iļģuciems, and the Correctional Institution in Cēsis. Each prison is, of course, its own story, just like in Croatia. This is always confirmed by a statement I once heard from a female inmate in a Croatian women’s prison: "We are a small Vatican." It’s the same in Latvia. One of the first things I noticed in Latvian prisons were the small spaces where inmates in Liepāja spend one hour a day walking in circles, while the other 23 hours they spend in cells with their roommates. The security and rehabilitation staff all wear uniforms, so it was difficult for me to tell who was who. The prison gate is entirely inside the facility and extremely well-protected, unlike in Croatia, where the gate is a small shack in front of the fence, if there’s even a fence, with one or two prison guards inside.

I also noticed that the staff in every prison we visited were incredibly friendly, open to working with volunteers and NGOs, despite being overworked, understaffed, and facing deadlines.

In reality, there aren’t many differences between Croatian and Latvian prisons, aside from some architectural variations and the friendliness of the staff.

The inmates and juveniles I worked with were very polite, although some individuals weren’t as enthusiastic about participating in the workshops and needed extra motivation. However, they gave their best effort and were respectful. Again, this varies depending on the institution, group, categories, number of participants, and many other factors. Maybe I’m wrong, and it seemed like they were more polite than those at home because I don’t speak Latvian or Russian. One significant experience was leading a workshop with such a language barrier, even with translators. Establishing a connection is much more challenging, but it’s possible. If you haven’t tried it, I highly recommend it. It’s tough.

A new mega-prison is being built in Liepāja, so I believe that inmates will have more humane conditions, more space for rehabilitation, including physical movement, gardening, working the land, fresh air, and many other benefits. I don’t think we can talk about rehabilitation or resocialisation until people can go outside, breathe fresh air, and walk around. No artistic workshop will ever replace that.

Croatian correctional institutions could show a bit more gratitude toward NGOs and others who are willing and enthusiastic about working with these institutions and their inmates. In Latvia, I noticed that the staff greatly appreciate any offer to spend quality time with their inmates, teach them something new, or even just sit at a table and talk for three hours. The inmates are also grateful. And let’s not forget that they are part of our society and that we need to engage with them. They’ve always been part of society, and they always will be. Outside involvement in prison work is essential because both sides benefit from a new perspective. If we are serious about rehabilitation, not just punishment, the work of NGOs, volunteers, artists, activists, and even anarchists—anyone who brings quality into the lives of inmates—is crucial while they are serving their sentences.

The job shadowing project is financed by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union that in Latvia is administrated by The Agency for International Projects for Youth.

This publication reflects only the viewpoint of the author.